Korte nieuwsflash op de voorpagina

Ik kreeg een verhaal onder ogen van een zeer intelligente man, maar wel iemand die bewust zijn zelfstandig denken uitzette toen het er toe deed. Iets wat we nu in de VS ook veelvuldig zien…

Lees hier het verhaal over Malcolm Caldwell.

———-

London, 1975. Malcolm Caldwell stood before his students at one of Britain’s most prestigious universities, doing what he loved most—teaching about revolutionary movements transforming Asia.

At 48, this respected scholar had built his reputation on a simple conviction: developing nations deserved to reject Western economic domination and create their own futures. He wasn’t wrong about Western imperialism’s damage. He wasn’t wrong about the need for change.

But he was about to become catastrophically wrong about something else.

April 17, 1975. Communist forces called the Khmer Rouge marched into Cambodia’s capital. Within hours, they forced two million people from the city at gunpoint. Hospitals emptied mid-surgery. Patients died in the streets.

Reports began emerging. Mass executions. Forced labor. Starvation. The Khmer Rouge was abolishing money, destroying temples, and executing anyone educated—teachers, doctors, even people who wore glasses.

The world reacted with horror.

Malcolm Caldwell reacted with admiration.

He saw something he’d been waiting for his entire academic career—a poor Asian nation completely rejecting Western capitalism. When refugees described atrocities, he dismissed them as CIA lies. When journalists showed evidence, he called it imperialist propaganda.

In lectures and journals, he defended the regime. ‘They’re building a new society,’ he wrote. ‘Western criticism is interference.’

He became the Khmer Rouge’s most prominent defender in the West.

Colleagues tried showing him evidence—testimonies, photographs, satellite images of abandoned cities. He rejected everything.

He believed what his ideology required him to believe.

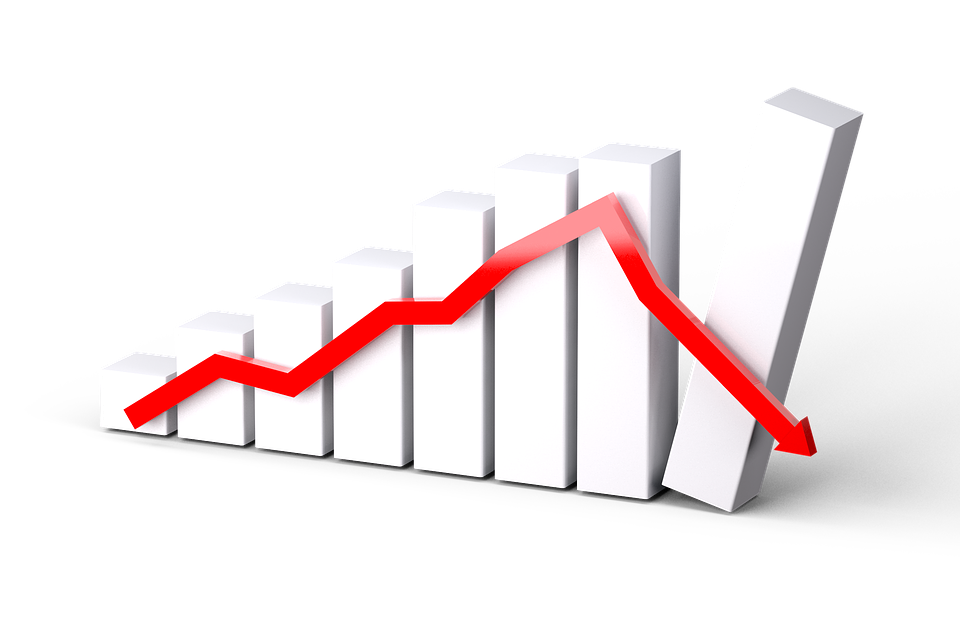

By 1978, Cambodia had become a closed prison. Nearly a quarter of the population—approximately 1.7 million people—were dying from execution, starvation, and forced labor.

Then Caldwell received an invitation.

The Khmer Rouge wanted to prove their success to Western intellectuals. They invited three people: Caldwell, and two American journalists, Richard Dudman and Elizabeth Becker.

For Caldwell, this was vindication. He’d finally see the revolution he’d defended.

December 8, 1978. They arrived in Phnom Penh.

What they saw was theater. The regime had staged everything—villages stocked with food, healthy-looking people giving rehearsed answers.

Becker and Dudman immediately noticed inconsistencies. People looked terrified. Stories sounded scripted.

Caldwell saw confirmation of everything he’d believed.

The tour culminated on December 23. They were granted an audience with Pol Pot himself—one of the world’s most secretive leaders.

The meeting lasted three hours.

Pol Pot explained his vision. He denied mass executions. He described the evacuation of cities as necessary defense against imperialism.

Caldwell believed every word.

Becker and Dudman left disturbed. They’d asked difficult questions, and Pol Pot had grown visibly angry.

Caldwell left exhilarated. ‘This is the most impressive thing I’ve ever seen,’ he told them. ‘A genuine revolution.’

They returned to their guesthouse. Late evening. Exhausted, Becker and Dudman went to their rooms.

Caldwell went to his room energized, already planning articles defending what he’d witnessed.

Around 1:00 AM, gunfire erupted.

Automatic weapons. Shouting in Khmer. Running footsteps.

Then silence.

Morning came. Khmer Rouge officials, visibly shaken, knocked on doors.

Malcolm Caldwell was dead. Shot once in the chest.

They claimed not to know who did it. There would be no investigation. Becker and Dudman were immediately driven to the airport and expelled from the country.

They never got answers.

Caldwell had traveled halfway around the world to meet his hero. He’d spent three hours with Pol Pot.

Twelve hours later, he was dead.

The timing was devastating.

December 23, 1978: Caldwell murdered.

December 25, 1978: Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia.

January 7, 1979: Phnom Penh fell. The Khmer Rouge collapsed.

When Vietnamese soldiers entered the city, they found what Caldwell had spent years denying existed.

Tuol Sleng—a torture center with documented records of 14,000 people interrogated and executed. Photographs of every victim. Meticulous documentation of systematic murder.

The killing fields—mass graves containing hundreds of thousands of bodies.

Survivors—emaciated, traumatized people describing years of forced labor, starvation, executions for minor infractions.

A nation where one in four people had died.

Everything the refugees said was true. Everything the journalists reported was true. Everything Caldwell dismissed as propaganda was true.

He’d died defending genocide.

Historians still debate who killed him. An internal purge? A message to the West? Did he learn something that made him dangerous? Was it random violence in a regime built on violence?

Nobody knows.

But here’s what we do know: Malcolm Caldwell wasn’t stupid. He wasn’t ignorant. He had access to the same information as everyone else.

He chose not to believe it.

He’d built his entire career on a worldview where Western imperialism was the primary evil and socialist revolutions were inherently liberating. Admitting the Khmer Rouge was committing atrocities would have meant admitting his framework was wrong.

It would have meant admitting he’d defended mass murder.

So he rejected the evidence. He reframed atrocities as lies. He chose ideology over reality.

And when he finally saw Cambodia, he saw only what he’d prepared himself to see—because seeing the truth was intolerable.

That’s the real tragedy.

Not the mystery of his death. But how he chose to live.

Today, the Cambodian genocide is documented beyond question. Tuol Sleng is a museum. The killing fields are memorials. Survivors have spent decades telling their stories.

And Caldwell’s name appears in histories as a cautionary tale—proof that intelligence offers no protection against self-deception when ideology becomes identity.

There’s a broader lesson here about all of us.

About how certainty can become dangerous. About how commitments to beliefs can make us reject obvious truths. About how smart people can defend the indefensible when admitting error feels impossible.

What evidence are we ignoring right now? What truths are we rejecting because they contradict what we want to believe?

Malcolm Caldwell died on December 23, 1978, under circumstances that remain mysterious.

But his intellectual and moral death happened years earlier—when he decided defending his worldview mattered more than acknowledging 1.7 million people’s suffering.

That’s the part worth remembering.

Not who killed him. But how he chose to live.

In memory of the 1.7 million victims of the Cambodian genocide whose suffering was denied while they died—and whose truth was revealed only after their defender was gone.